Our History

Our History & Charitable Status

Built in 1869, Cirencester Open Air Swimming Pool first opened to the public in 1870, 155 years ago.

Throughout its lifetime, the pool has needed significant repairs and refurbishment in order to maintain this wonderful community resource – and our entrance money goes a long way towards its upkeep.

But for special projects, more money is needed so our charity relies on alternative means of support like charitable gifts and donations, grants, volunteers and sponsors.

The following articles have been written by local Cirencester people on the history of the pool.

A Brief History of Past Times at The Baths written by Barbara Chamberlain, April 2020

‘Beckwith is coming’ ran the teaser in the Wiltshire and Gloucestershire Standard of 8 August 1874, heralding an announcement the following week that the services of Professor Beckwith and his self-styled ‘Beckwith frogs’ family would perform their wonderful feats of ornamental swimming, diving & floating in Cirencester Swimming Baths.

Whilst it might seem odd to us that people would pay to watch the demonstration of perfect swimming strokes, at this time few people could swim, and those who could were able to make a good living by swimming demonstrations and vaudeville shows. ‘Professor’ Beckwith was a celebrated sportsman who staged elaborated demonstrations of swimming and brought his children into the act.

Reports of the day confirmed the extremely novel event was an unqualified success, observed from a large temporary grand stand by distinguished visitors and a large number of ladies. Professor Beckwith, for many years the Champion swimmer of England, opened proceedings and plunged in attired in a full suite of clothes, which he removed, garment by garment, landing them safely on the bank, amid applause. He demonstrated long and steady swimming strokes, then, to much laughter, illustrated the amusing attempts made by learners to swim, after which he went up and down the bath in a peculiar manner known as ‘waltzing’. Thirteen-year-old Miss Agnes Beckwith, “the mermaid”, the most accomplished lady swimmer in England, gave her display of ornamental swimming and floating, some of which was adjudged ‘very excellent’. Young William Beckwith, considered the third best swimmer in England and the champion swimmer of The Serpentine, gave an exhibition race of fast swimming, before gallantly rescuing his father, who was impersonating a drowning man, in the most approved fashion. The report praises the enterprising and energetic committee, noting that ‘the Bath has become such an institution of the town that description of it is entirely needless.’

One imagines the gratification of Mr Thomas Cox and his fellow entrepreneurs who, in 1859, embarked on the project to create a Public Bath in Cirencester, countering opposition from such as the millers to the use of the water. Eventually, in 1869, the Cirencester Baths Company Limited was formed, proposing the Bath as a sanitary agent for a population of 6,000, deriving income from annual subscribers and the public, anticipating a handsome dividend on the capital invested. In May 1870, the Swimming Bath, ‘as fine as any in the kingdom’, opened, with good attendance from the general public, although the cold easterly winds initially deterred the ladies from frequenting the ‘Corinium Baths as Roman ladies did of old’.

The successful 1874 Gala was the first of many over the years up to the First World War, during which a Swimming Club was established and Water Polo matches were played against teams from Cheltenham, Stroud and Gloucester. In 1912, the ornamental swimming champion of the world, Miss Florence Tilton of Gloucester, gave an exhibition which included drinking a bottle of milk under water, eating a banana under water, sewing under water, ‘seal at play’, ‘the porpoise’ and swimming like a fish for one length of the bath.

In 1908, Cirencester Urban District Council took over the Baths, which were emptied of water on a Saturday evening and refilled during Sunday from the adjoining well. Hardy bathers in the early part of the week endured ‘icy cold water’ until it gradually attained a more tolerable temperature.

The Council decided to improve the facilities and, in 1931, hosted a re-opening ceremony heralding the installation of a heating system to maintain the water temperature at not less than 60 degrees (around 15 degrees Celsius), a shallow pool for young children and dressing boxes for both males and females to enable arrangements to be made for mixed bathing under proper regulations. A kiosk opened soon after selling soft drinks, buns, cups of tea and cigarettes.

1936 brought a technological development eloquently described in the Wiltshire and Gloucestershire Standard as attributing ‘an unusual glint on the water which was of an unaccustomed limpidity.’ The ‘water’s pellucidity’ resulted from a new purification plant, placing the Cirencester Baths in line with the best in the country. The article explained that the water is filtered in a huge tank containing 11 tons of special sand, then ‘aerated’ to give it life, before being sterilised via a process of chlorination, ‘a process so delicate that its results are calculated in decimal points’. ‘The result is conditions as hygienic and salubrious as modern science can make them, while bathers experience a tonic effect entirely lacking before’.

Over the following decades, the Swimming Club and Water Polo teams continued to thrive, promoting life-saving skills and encouraging people of all ages to learn to swim. Local schools used the facilities, leaving some pupils with enduring memories of enforced chilly swimming lessons.

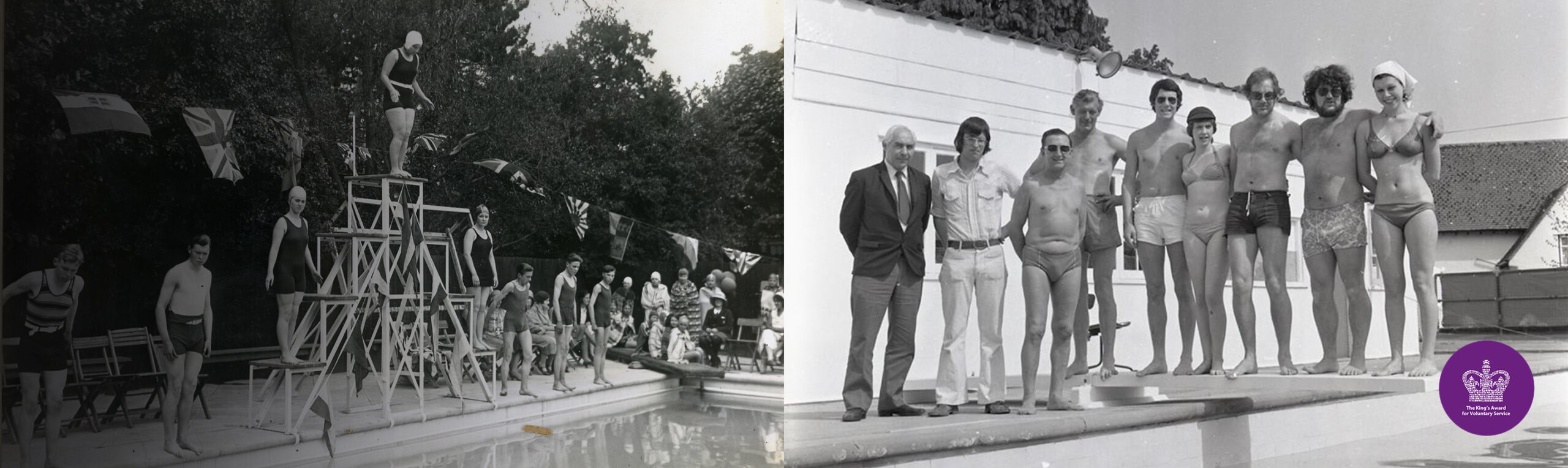

In the 1970s, further repairs were needed and, in 1972, the Council built the indoor swimming pool, proposing to close the outdoor baths. Substantial opposition culminated in the Council handing the outdoor pool over to the ‘Open Air Swimming Association’ for a peppercorn rent, and this formidable group of volunteers somehow ensured the continuing operation of the pool and developed a more structured organisation. In 1983, charitable status was granted, and succeeding trustees continued the sterling work to make the operation more sustainable. A major fund-raising exercise in the 2010s, generously supported by many organisations and individuals in the community, culminated in the opening of new changing rooms in 2016, followed by the addition of pool covers (to help reduce heating bills) and improved access to the site for disabled people.

Today

150 years after Cirencester Baths first opened, we continue to welcome visitors to enjoy the idyllic facilities, including the popular kiosk, now known as the Tuck Shop. Water is still drawn from the original well, purified via the filter tank installed in 1936, though now it is heated to around 25 degrees Celsius. ‘Dressing boxes’ are now the changing rooms that were built in 2016, which include hot showers and disabled facilities while mixed bathing is now taken for granted. Advertising regulations restrain us from promising a ‘tonic effect’ from immersion in the limpid water although several of our regular swimmers describe the pool as their ‘happy place’. Our trained life guards encourage everyone to enjoy their visit whilst observing sensible, modern safety policies, which necessarily exclude some of Professor Beckwith’s and Miss Tilton’s ‘fancy’ frog feats.

Since 1973, dedicated volunteers have taken responsibility for organising day-to-day operations during the summer, and maintenance and fund raising during the winter. The only paid staff are the life guards and any specialist service providers needed for the maintenance of the pool.

Cirencester Open Air Pool Memories by C.W. MaslimPic – The Water Polo Team of 1938

I well remember the Cirencester Open Air Swimming Pool as far back as the late 1920s, when the cost of a season ticket was only a few shillings and there was no mixed bathing. The pool would close, I think, at 6 pm on Saturdays to enable Mr James (who was the pool attendant) to empty and clean the pool, ready for it to be refilled with fresh and very cold water from an adjacent well each Sunday. In those days, Sunday bathing was not permitted and changing cubicles lined the pool on both sides.

Early in the 1930s, things changed : mixed swimming was permitted and the water heating and purifying systems were installed – some of which equipment is still in use today, I believe. It was around then that Mr Eric Cole started the Swimming and Water Polo Club which received excellent support from many quarters. A water polo team was formed and it entered the Three Counties League where, after a few seasons, it began to meet with quite some success. Matches were played against teams from Bristol, Gloucester, Cheltenham, Swindon, Hereford, Chippenham, Stroud, Worcester and Evesham. At Stroud, we used to play in the canal and at Chippenham, in the river, before both clubs had their local swimming pools installed.

I have been told that a photograph of the 1938 water polo team is on display in the Cirencester Museum. (I have never thought that I would become a museum piece!)

In the latter 1930s, a winter bathing group was started and, on many occasions, I well remember us having to break the ice across one end of the pool before we could have our swim. I recall the first morning when ice covered the pool and Archie Hughes dived in without clearing the ice away; as a result, he received rather bad cuts about his body which necessitated hospital treatment.

On another winter’s morning, we received a visit from a member of the local police force who said that a resident in the barracks at Cecily Hill had complained that she could see us running around the swimming baths in the nude. As we were screened by the changing booths, we never wore any costumes for our dip and we used to run afterwards to set up a wonderful glowing feeling. That being the case, the officer went to her flat to investigate. On looking out of her window, he told her that he could not see the pool to which she replied, “Oh! You have to stand on that chair!”

I understand that the pool is no longer owned by the local council but is managed by a consortium of local people to whom I wish every success for the future.

Our Journey So Far by Winifred Waites

Pic – Lady at the pool / Early Pool Swimmers, 1913

It was in May 1869 that a group of businessmen in Cirencester endeavoured to promote a private enterprise that was to benefit Cirencester town right up to the present day, well over a hundred years ago. They had conceived the idea of providing a “swimming bath” and approached Lord Bathurst for help in finding a suitable site. Finally, it was decided that the best place was the meadow at the rear of Barracks Yard, which was approached by way of a footpath from Thomas Street, beside the stream leading to the mill in Barton Lane.

Lord Bathurst also made a donation of £25 towards the scheme and a prospectus for launching a limited company was published, offering shares for sale at £5 each. Apparently, the project was regarded with much favour as, within a day or two, a large proportion of the shares were taken up. On 10th July 1869, the company was registered with limited liability and the directors appointed to act until its first general meeting were:

Mr. Anderson

Mr. T. Cox (who may have been the second husband of Daniel Bingham’s mother) – Secretary

Mr. C. Hoare, junior.

Mr. Mildred

Mr. John Mullings

Mr. Newmarch

Mr. Parry

and Mr. Zachary.

In September 1869, the directors held a meeting at which it was decided to enter into a contract with a Mr. James for the building of the swimming pool. Mr. James had already built a bridge over the stream, giving access to the site and although his was not the lowest tender, it was felt he would make an excellent job of building this bath, “so noble in its proportions”. Moreover, they added, it would be a great ‘boon’ to the inhabitants and no doubt the forerunner of other sanitary and hygienic improvements. The report of this meeting appeared in the local press and inspired a letter from someone who signed himself Y.Z. He pointed out that a boon was a gift or a present and, since the shareholders were conducting the affair on a commercial basis and obviously hoped to receive a good return on their money, the only ‘boon’ given to the town was from Lord Bathurst who had not only donated the land but also £25 toward the project.

Built during the winter of 1869/70, the swimming bath was ninety feet long by forty-five feet wide and contained 100,000 gallons of water, which was pumped by steam power from a near-by spring. It was well constructed, being lined with white glazed bricks, and it had a springboard at one end and dressing boxes along the side. In due course, the pool opened and it continued to function for the next few years – but whether the shareholders reaped any interest on their investment is not known and I suspect not.

Steps were taken in 1884 to form a swimming club, and excellent contests took place, for which prizes were given. Nevertheless, the swimming bath project was never wholly successful and, as repairs became necessary, it was used less and less as the years went on. On the 30th May 1896, the Cirencester Urban District Council set up a committee to consider the feasibility of providing public swimming baths and whether the existing pool could be repaired satisfactorily. New sites were discussed but, as the original shareholders were willing to wind up their affairs, it was decided the council would take over the existing pool in accordance with the Baths and Wash-houses Act.

When I first went to the pool in the 1920s, the pool was filled every Sunday morning and emptied every Saturday evening. At the start of the week, the water would be clean but the temperature would be painfully low : about 58 degrees if you were lucky but it was more likely to be 55. By the end-of the week, the temperature might have crept up to the low 60 degrees if it had been warm but, because there was no chlorination or water circulation, the pool would get increasingly dirty until by Saturday afternoon, the water would be covered with a green slime and full of leaves.

In those days, there was no mixed bathing so, at the allotted times for ladies on Tuesdays and Fridays (which allowed a maximum of forty-five minutes onsite and no more than twenty minutes in the dressing boxes), we schoolgirls used to march in a crocodile from the grammar school in Victoria Road to the swimming baths, carrying under our arms our neatly rolled towel with a bathing costume and cap. Our navy costumes were all one piece, modestly starting around the neck and reaching down to the knees, leaving a minimum of thigh visible. Plunging into the icy water – under the watchful eye of the teacher – was an ordeal indeed. We stayed in the water for fifteen or twenty minutes and, to the beginners who could not swim, this seemed an eternity. Wet and shivering, we endeavoured to dry ourselves in the allotted ten minutes and, even now, I can still feel the cold damp of my partially dried body and the numbness of my posterior as we marched back to school. We were not allowed to run, which might have warmed us up, as that was not considered ladylike.

That first summer, I learned to swim a few puny strokes… I discovered that, being a grammar school girl, I automatically had a season ticket so whenever tile weather was suitable, I spent a considerable amount of time at the pool during the long summer holidays. Lots of other girls did the same and we had some jolly times. Most of them were much stronger swimmers than I was so they spent their time jumping or diving in at the deep end. I looked on, wishing I could do the same, until one girl, Vera Porter – who lived in the Barracks, the great bastion which overlooks the pool like some benevolent watch-dog – said to me “Oh come on, jump in with us, we’ll all hold hands”. Trustingly, I did so but of course as soon as they were in the water, they let go of my hands and swam for the side, leaving me spluttering and choking and trying frantically to coordinate my ineffective strokes. It was a very long time before I ventured into the deep end again.

In 1931, the lease of the land from Lord Bathurst expired so the Urban District Council decided to purchase it and to carry out many improvements. They added a shallow pool at one end for small children and installed a heating system, sufficient to ensure that the temperature never fell below sixty degrees. Extra dressing boxes were built, enough to accommodate male and female swimmers at the same time so that mixed bathing was possible. The water, ‘now taken from the town’s supply’ was chlorinated and circulated – and with that, the hey-day of the outdoor swimming pool began. A very strong swimming club and a water polo club were formed. Tiers of seats were placed around the pool’s edge for spectators on the many gala nights. What’s more, a deck for sunbathing was laid out on the roof of the store and engine rooms, behind the diving tower at the deep end.

Once a kiosk was opened for selling soft drinks, buns and cups of tea, quite a busy social life developed around the pool. On warm summer days, people went there to meet friends, to sit and read, or to watch the swimmers and more spectacular divers. Mothers took their children after school, complete with picnic, and chatted whilst their offspring splashed about in the children’s pool. Apart from the fact there was no sand, it was, as one Mother said, “just like the sea-side”.

Then came the Second World War. The pool was now more popular than ever, as service men stationed in the district made good use of it, and generation after generation of Cirencester boys and girls learned to swim in it. Over the years various alterations took place. The entrance was changed to the northern end of the pool, and the general layout of dressing boxes altered to better advantage. The diving tower was removed because it was deemed too dangerous to dive from such a height into only six feet of water yet in all the years the tower was used, I never heard of anyone being hurt.

Just as the pool was reaching its centenary, it was found that a lot of water was being lost daily, supposedly because the concrete base had cracked and was beyond repair. The heating system was not too reliable and so many other things needed attention that the council decided to replace the old pool with a new indoor one. Much discussion with the townspeople took place, much of it heated, but plans for a new indoor pool were put in hand and all but completed by I972.

The old pool that had served the town so faithfully for over a hundred years was under sentence of death. But the people of Cirencester were loath to part with it : there were meetings voicing opposition, petitions and letters to the local press while local councillors were lobbied on all sides to keep the old pool open. “Why not keep both pools going? ” they argued. “Too expensive” came the reply, “besides, the old pool has broken its back and is beyond repair”.

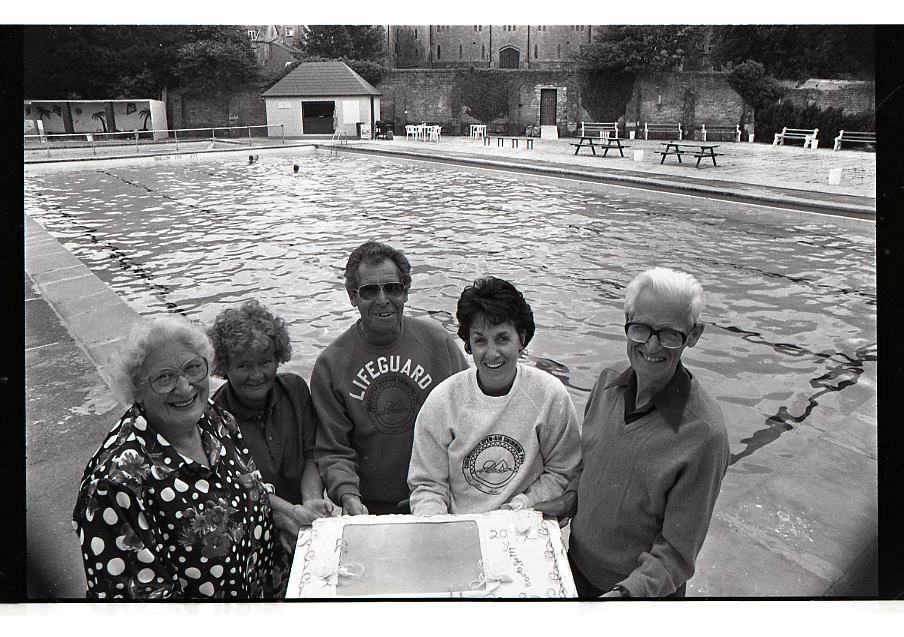

However, a little band of open-air swimmers refused to give up. At a council meeting in May I973, to which the representatives of the Outdoor Swimming Pool Group had been invited, it was suggested that, for a peppercorn rent, the swimming group might like to run the old pool themselves. Undaunted by the considerable repairs the pool might need, they accepted the offer.

A letter was sent to the local press, advertising the pool and asking for season ticket subscriptions at three guineas each, in the hope this would raise enough money to meet running expenses for the summer. They were doomed to disappointment. The response was far lower than expected and it seemed, after all the hard campaigning, that the pool would have to go. Then magically, almost like a fairy tale, a lady from a nearby village who enjoyed outdoor bathing offered to stand surety for the running of the pool up to one thousand pounds. Immediately, the swimming pool committee set to, with many of its retired members and pensioners all helping to clean and paint and repair wherever was necessary, including a leaky pipe in the ladies’ toilets. As soon as this was repaired, the heavy loss of water ceased – meaning the pool had not broken its back after all. The Open Air Swimming Pool Association (as they called themselves) felt all was well and proceeded with renewed energy.

To save water rates, they reverted to using the well water first utilised by the original bath company except that now the water was heated, which made the water feel delightful and as soft as rose petals on the skin. Numerous money making activities were devised all summer long, such as rummage sales, dances and galas and, at the end of that first season, the gallant little band of campaigners emerged having not touched a penny of the thousand pounds surety and with some money still in hand.

The following summers were not always so good. A new heating system had to be installed and new changing rooms built to replace the rotting boxes, along with many other improvements. Nevertheless, through ingenuity and hard work, and by voluntarily manning and maintaining the pool, they kept this historic feature going. Over a hundred years since its fine outdoor pool was built in 1869, by private enterprise, Cirencester still has this wonderful facility because, rather poetically, it has been kept going by private enterprise.

It is the marvellous success story of a courageous little band of people who stood firm against bureaucracy and by whose efforts Cirencester was able to retain a popular amenity, which costs the ratepayer nothing at all.

On fine, sunny summer mornings, when I jump into that inviting blue water, soft as silk, with the blue sky above, the sun on my face, the birds singing and the lap of the water as I swim, I am so grateful to them. As I look up and see the massive walls of the Barracks towering over the pool and peer through the trees to the tower of the parish church, I realise it must have been just like this over a hundred years ago when the first swimmers enjoyed this pool…

I sincerely hope it will remain so for another hundred years and that future generations of Cirencester people will gain as much pleasure from it as I have.